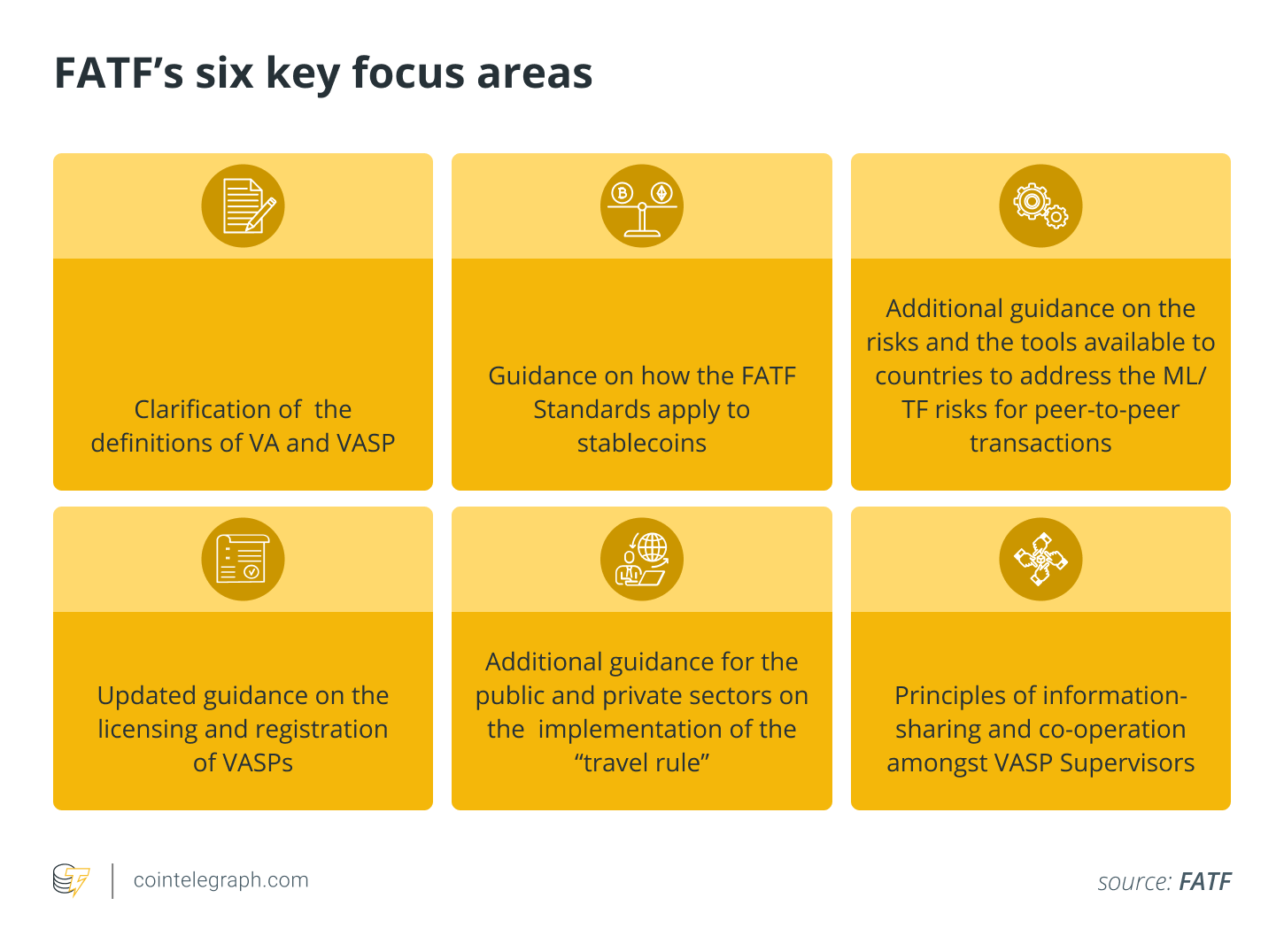

The current Eu proposal requiring centralized crypto exchanges and custodial wallet providers to gather and verify private information about self-custodial wallet holders shows the risks of recycling traditional finance (TradFi) rules and applying these to crypto without appreciating the conceptual variations. Don’t be surprised to determine much more of this as countries turn to implement the Financial Action Task Pressure (FATF) Travel Rule, initially designed for wire transfers, to transfers of crypto assets.

The (missing) outcomes of self-child custody, control and identity

The purpose of the suggested EU rules is “to ensure crypto-assets could be tracked in the same manner as traditional money transfers.” This assumes that every self-custodial wallet could be associated with someone’s verifiable identity which this individual always controls the wallet. This assumption is wrong.

Related: Government bodies are searching to narrow the gap on unhosted wallets

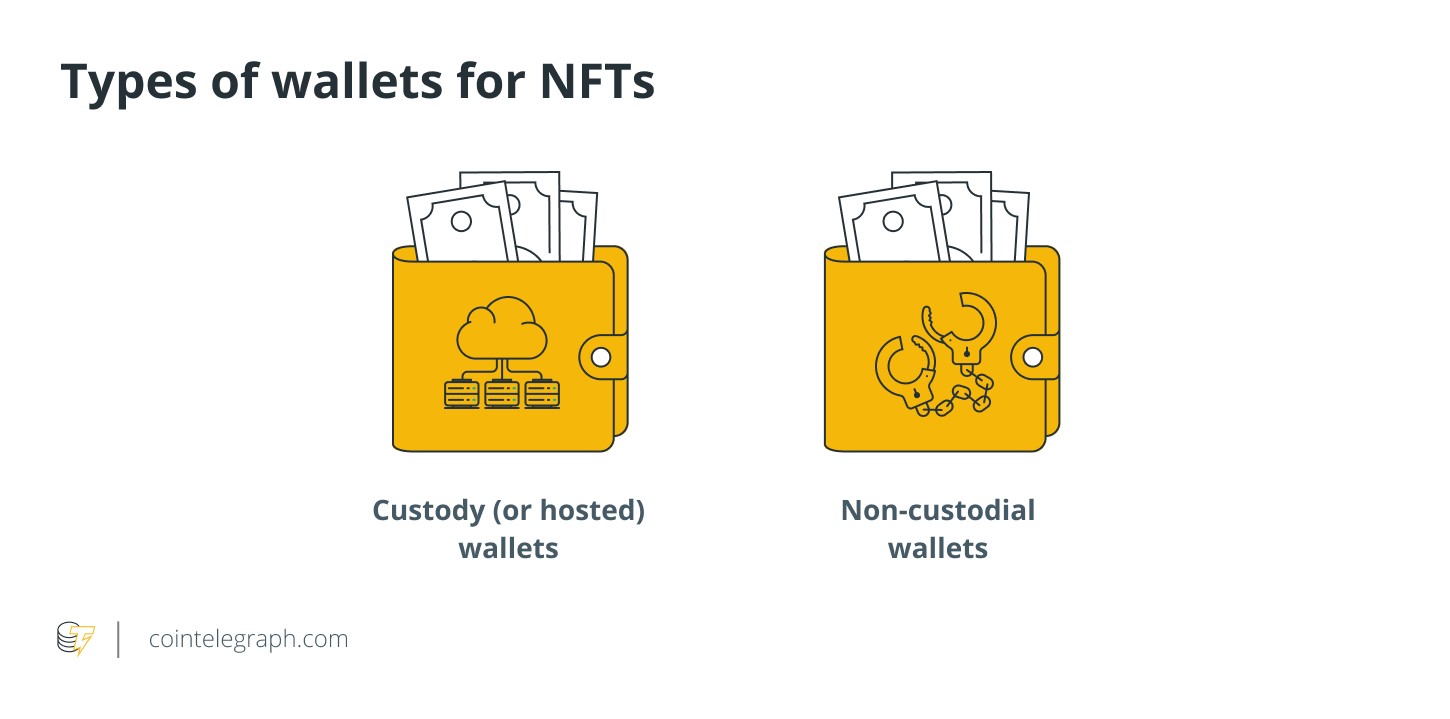

In TradFi, a financial institution account is from the verified identity of their holder, providing them with control of that account. For instance, discussing your web banking details together with your partner doesn’t make sure they are the account holder. Even when your lover changes the login details, you are able to get back control by showing your identity towards the bank and getting it reset the facts. Your identity provides you with ultimate control which can’t be permanently stolen or lost. Obviously, in return for the bank’s child custody protections, you lose self-sovereignty over your assets.

Self-child custody of crypto assets differs. Control (i.e., the opportunity to transact) within the self-custodial wallet takes place by whomever has got the private secrets of that wallet. Control isn’t associated with anyone’s identity and there’s nobody to demonstrate your identity to. You just need to download a bit of software and securely store your private keys. In return for this responsibility, you maintain self-sovereign possession.

Applying the suggested rules

Let’s take a look at the way a custodial wallet provider would start submission using the EU proposal. Think that Alice really wants to send .3 Ether (ETH) from her custodial wallet account to Bob’s self-custodial wallet to cover Bob’s talking to services. Prior to the transfer experiences, the custodial wallet provider would need to 1) collect Bob’s name, wallet address, residential address, personal identification number, and date and put of birth and a pair of) verify the precision of those details. Broadly exactly the same details could be needed for any transfer from Bob’s wallet to Alice’s custodial wallet account. Alice may likely have to ask Bob to transmit her his details, and Alice would then provide these to the custodial wallet provider — as lately suggested with a custodial wallet provider inside a similar context.

The guidelines would apply even going to the tiniest transactions — there’s no minimum threshold. Custodial wallet providers would conceivably should also withhold incoming transfers (creating greater child custody risks) and send them back towards the self-custodial wallet when the verification is not successful.

Related: Crypto in Canada: Where shall we be today, where shall we be heading?

Identity doesn’t equal control, making compliance impossible

While collecting data and potentially withholding incoming transfers is operationally cumbersome, the verification obligation risks are potentially outright impossible to conform with. In TradFi, the purpose of identity verification is to make sure that the individual controlling a financial institution account and claiming to do this is identical one. But exactly how is the custodial wallet provider match the verification obligation if control of Bob’s self-custodial wallet doesn’t rely on his identity?

Whether or not the custodial wallet provider were able to make sure Bob may be the person he proposes to be, this doesn’t imply that he controls the wallet. It may be controlled with a decentralized autonomous organization that redistributes payments to people like Bob or perhaps a criminal group, with Bob just being their cash mule. There’s no 3rd party to demonstrate Bob’s identity to to be able to transact — whomever controls the non-public keys may be the “bank.”

Exposing legitimate users to disproportionate security risks

Let’s think that custodial wallet providers have the ability to adhere to the suggested rules, or perhaps a less stringent form of them that doesn’t require verification. Custodial wallet providers will have to keep large databases of self-custodial wallet users, exposing users to the chance of data breaches. For legitimate users, i.e., individuals who declare their true identity as well as really control the attached self-custodial wallet, this risk has much better effects than TradFi data collection (e.g., FATF’s Travel Rule for wire transfers).

In TradFi, if your criminal compromises someone’s banking account or card, they wouldn’t end up with far since the bank can block the account. Obviously, self-custodial wallets lack this selection. Self-sovereign possession, guaranteed through cryptography and also the user’s own vigilance, is viewed as a benefit by millions of users worldwide, including individuals who’re excluded in the banking system. However, self-sovereignty presumes security.

Once privacy is compromised — for instance, by hacking the custodial wallet provider’s database of self-custodial wallet users — users remain uncovered for an unfair degree of risk when compared with TradFi. Knowing someone’s name, address, birth date and ID number, along with their on-chain activity, will make it simpler for crooks to launch highly personalized phishing attacks, targeting users’ devices to retrieve private keys, or blackmailing them, including threats to physical safety. Once private keys are compromised, the consumer irreversibly loses control of their wallet.

Related: Losing privacy: Why we have to fight for any decentralized future

Since crooks will discover ways round the rules — for instance, by running their very own nodes to have interaction using the blockchain without ever getting to depend on custodial wallet providers or self-custodial wallet software — it are only the legitimate users who will need to bear these security risks.

Inconsistencies with EU’s own policy framework

Security aside, the proposal raises broader privacy concerns. The reporting obligation would clash with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) concepts for example data minimization, which mandates that collected data are sufficient, relevant and limited to what’s necessary with regards to collecting them. Ignoring as it were the argument that data collection serves little purpose, because of the missing outcomes of self-custodial control and identity, it’s difficult to see — even by TradFi’s standards — how someone’s residential address, birth date and ID number is pertinent or essential for creating a transfer. While banks regularly keep such data regarding their customers, you because the account holder do not need to inquire about (and know!) these records when delivering money or having to pay for any service.

It’s also unclear for the way lengthy custodial wallet providers will have to keep data — under GDPR, private data ought to be stored just for as lengthy as essential to fulfil the objective of collection. Neither is it obvious how users’ individual legal rights under GDPR like the “right to become forgotten” and also the “right to rectification” might be respected if their personal information are associated with their on-chain history, which can’t be altered.

Related: Browser cookies aren’t consent: The brand new road to privacy after EU data regulation fail

The possible lack of any risk-based assessment or perhaps a minimum threshold (unlike the fir,000 euro threshold for fiat transfers) can also be from line with EU policy concepts. The proposal appears to deal with all crypto transfers with suspicion simply because they require crypto assets.

This is the time to interact with policymakers

Confronted with the possibilities of developing pricey compliance processes that will likely neglect to effectively implement the guidelines, and risking penalties for non-compliance and potential data breaches, EU-based custodial wallet providers might wish to restrict transfers to and from self-custodial wallets altogether. They might also start servicing EU users from outdoors the EU. This transmits bad signals towards the crypto industry and risks discouraging tech talent and capital in the EU, like the recent departure of some crypto operators in the Uk.

Related: Consolidation and centralization: How Europe’s new AML regulation will affect crypto

More users might also change to peer-to-peer transactions and decentralized players to prevent the troublesome rules. While this may be advantageous for many users, the EU should encourage smooth interconnectivity between centralized and decentralized players and promote users’ freedom to select how they would like to transact.

The proposal has gone to live in negotiations between your EU legislative physiques beginning April 28, using the final text expected through the finish of June. When the rule passes in the current form, there it’s still an opportunity to evaluate it within 12 several weeks after its entering pressure. However, we can’t depend about this — this is the time for that European crypto industry to coordinate and interact with policymakers. Rather of intentionally applying TradFi rules to some developing technology, we ought to promote outcome-based policies that permit the emergence of novel compliance solutions that respect how crypto works.

This short article doesn’t contain investment recommendations or recommendations. Every investment and buying and selling move involves risk, and readers should conduct their very own research when making the decision.

The views, ideas and opinions expressed listed here are the author’s alone and don’t always reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.

Natalie Linhart is really a a lawyer at ConsenSys, where she advises on products including MetaMask, NFT encounters and institutional staking. She also concentrates on European regulatory issues affecting the crypto industry. She formerly labored like a financial regulatory and derivatives lawyer at Clifford Chance London, counseling clients on launching lending options, being able to access untouched markets and mitigating regulatory risks. She also labored on derivatives and debt capital markets transactions including in a global investment bank.